Maybe it is that our ceiling fan is running again. Outside it is a stifling 84 degrees, in March. Or maybe it was the probing questions asked by an expectant mother yesterday. Regardless, I am brought back- back past the sleepless nights, the joyful milestones, and the hundreds of hours spent breastfeeding. Into the pain room.

0 cm.

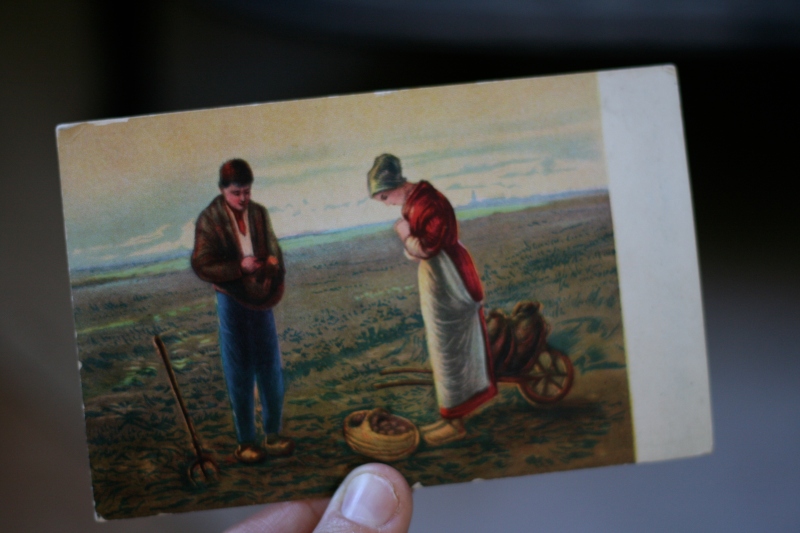

In love we conceived a baby but I don’t know where- maybe in our claustrophobic trailer, the one sitting on 40 acres of rocky unfertile land, or maybe one of the first blissful nights spent in the first home that would be entirely ours.

291 days later we had turned the calendar from July to August and I was 11 days overdue, only 3 days before we’d have to give birth in a hospital by law. Being overdue was okay by me, minus that it was too bloody hot outside. Although, I admit there was the impending hospital birth, the annoying phone calls, and that my sisters slated to be present for the birth had already come…and gone. Without a newborn to care for we had plenty of time to bake cakes, can ketchup and tomato sauce, and take lots of leisurely walks at the beach. Chris’ brother had also returned to China and his mother was on a pre-booked camping trip. It would just be Chris and I.

1 cm.

My water gave out at 2 am, neatly over the toilet. I was too excited to sleep. That morning we had baby chicks hatching- a surprise to us, the warning on our August calendar had gone unheeded. These were the first births of the day at our house.

Preparations were made. A tub set up. A frosty vegetable lasagna pulled out of the freezer for our soon-to-be ravished midwives. Fresh zinnias and sunflowers were brought in from the garden.

Later that afternoon, a door was opened and I entered a room. A room created at the beginning of time. One only females can enter, humans and animals alike. You could call it ‘laborland’ as my friend Kim does. But that is too understated and trivial a name for this room. Although it is otherworldly to be sure. My rite of passage had begun.

2 cm.

Chris and I slow danced in the bedroom. I hung from a sheet hung from our kitchen door, using it to brace myself with contractions. We watched West Wing together on Netflix while I hugged a birth ball in the living room, pausing the show when the pain was too strong for me to focus.

3 cm.

A tattooed, bearded man put needles in me- behind my ears, between my fingers, on my ankles and in other areas I don’t recall. I endured contraction after contraction alone on our couch, afraid to move or else disrupt the needles. I felt alone. Chris was somewhere, I don’t remember where. People were talking in hushed voices in the bedroom. I tried to be quiet.

4 cm.

The midwives said I could get in the tub. It was lukewarm. Chris got in with me. The contractions were coming now like waves, waves that could not be stopped no matter how hard I willed them to. Chris reminded me to relax like we practiced in our birth class. I tried but I could not relax. The water was so cold. I don’t want to have a baby anymore, I decided.

9 cm.

They told me to feel for his head. He is stuck behind my cervix they said. Your cervix is inflamed they said. Take these homeopathic pills for the inflammation they said. Get on the bed and put your butt in the air they said. Get back in the tub they said. Eat these scrambled eggs and honey they said. Vomit in here they said. Move to the bathroom they said. Slow down your breathing they said.

10 cm.

My whole body shook. There was no rest between contractions, only time to gasp for air. Hour after hour I grasped my husband by the shoulders and bared down.

Surely I was no longer journeying toward motherhood, but unto death. I wanted to die. Between contractions I brainstormed the many ways Chris could take me out of my misery. If only for the prison sentence! I fantasized about epidurals and hospitals and a place where there was no pain.

Finally I mustered the words that had haunted me for 291 days, the ones playing over and over in my head like a broken record with every contraction.

“I don’t know if I can do this.”

I squatted on the bed and a baby boy emerged from my body with my husband watching on. They gave him to me. I breathed in his mouth and he started crying. I felt so happy, but not to meet my baby.

I had clawed my way out of the pain room.